![]()

In this installment of "Where the Southern Cross the Yellow Dog," we take a sneak-peek look at an upcoming page that will eventually be on display to the public. As a Patreon supporter, you have access to the page one full year before the public does.

• Patreon Release Date: January 21st, 2022

• Public Release Date: January 21st, 2023

Please tell your friends that they can subscribe to my Patreon stream for $2.00 per week:

•

"It's All Ephemera with Cat Yronwode"

To discuss this and other Your Wate and Fate pages with me, join my private Patreon Forum here:

•

Private Patreon Forum for Where the Southern Cross the Yellow Dog

All of the material you have access to here -- the instructive booklets, the nostalgic postcards, the boldly graphic ephemera, and all of the historical information researched and shared from the mind of the woman who is making it all happen -- can easily fit into one 8 x 10 foot room in an old Victorian farmhouse, but you would never see it without the investment of the time it takes to produce such a site and the caloric input such a site requires in the form of food for the writer, graphic designer, and database manager, as well as the US currency needed to pay for the computers, software applications, scanners, electricity, and internet connectivity that bring it out of that little room and into the world.

So, as you can see, this site is the darling of many, and it is growing at a rapid rate

... but although it is "free," there also is a cost. The financial support of my Patreon

subscribers -- my Patrons -- underwrites this cost.

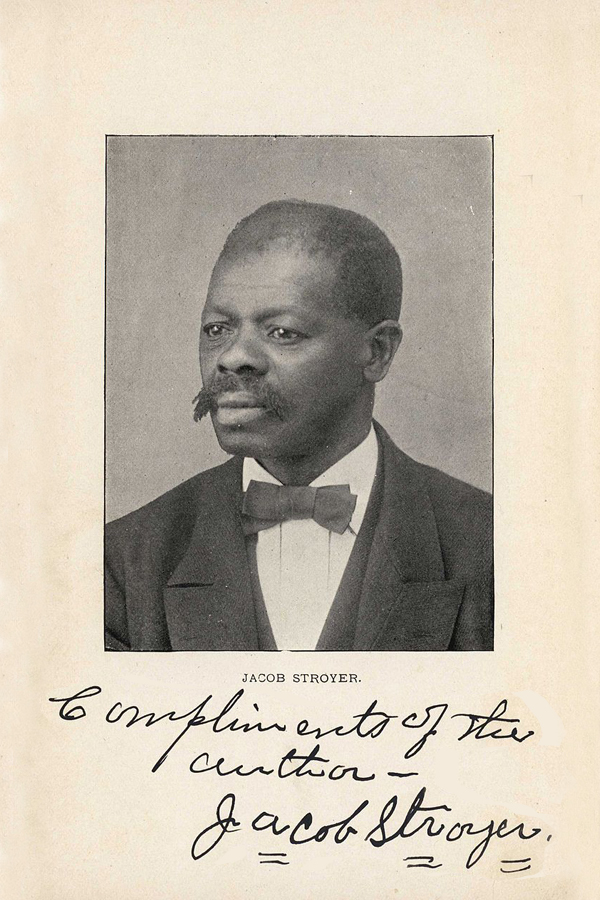

Jacob Stroyer was a man of African descent who was born in slavery in 1849 in Easrover, South Carolina. He remained enslaved until the Civil War ended in 1865, when he was about 16 years old. As a child he lived on a large plantation were almost 500 people of African descent were held captive. He worked as a stable-hand or hostler, caring for horses. He taught himself to read while young. Stroyer was a child during the era of slavery and he never attempted to escape. In 1863 when he was 13 years old, he was assigned to a Confederate Army work detail and a year later he was wounded by Union forces at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. By the time he fully recovered from his injuries, the Civil War had ended and he was emancipated.

After freedom came, Stroyer attended schools in Columbia and Charleston, South Carolina. Then, in 1870, at the age of 21, he left the South for Worcester, Massachusetts. He studied at Worcester Academy for two years and was licensed as a local preacher in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church. He relocated to Newport, Rhode Island, where he was ordained as a deacon, and then to Salem, Massachusetts, where he settled and worked as a minister. He died in 1908 in Salem, at the age of 59, from heart disease.

"Sketches of My Life in the South," Stroyer's autobiographical account of enslavement, was first published in 1879, when he was 30 years old. It was quite popular in its day and went through four revised editions until 1898. The entire book is worth reading, and it can be found online in digital form, but for our purposes here, i will begin with a few extracts from the beginning of the book to set the scene of who Jacob Stroyer was, and then proceed to two sections of the book that deal with metaphysical and folkloric matters of witchcraft and divination.

The text that follows draaws from the revised third edition of the book, and to make it easier to read, i have inserted line breaks rather than remain wed to the difficult-to-follow Victorian style of presenting paragraphs that run for a full page or more. Additionally, because this author used terms unfamiliar to modern readers or employed spellings not commonly found in the literature of hoodoo, a few explanatory notes have been added [in brackets].

I was born in the state of South Carolina, twenty-eight miles northeast of Columbia, in the year 1849; I belonged to a man by the name of Col. M. R. Singleton, and was held in slavery up to the time of the emancipation proclamation issued by President Lincoln [in 1863, although Stroyer, like many slaves, was not freed until 1865, at the surrender of the Confederacy].

My father was born in Sierra Leone, Africa. Of his parents, and his brothers and sisters, I know nothing, I only remember that it was said that his father's name was Moncoso, and his mother's Mongomo, which names are known only among the native Africans. He was brought from Africa when but a boy, and sold to old Colonel Dick Singleton, who owned a great many plantations in South Carolina, and when the old colonel divided his property among his children, father fell to his second son, Col. M. R. Singleton, the second son. Father was not a field hand, but used to take care of horses and mules, as the Colonel had a great many for the use of his farm.

I did not learn what name father went by before he was brought to this country, I only know that he stated that Col. Dick Singleton gave him the name of William, by which name he was known to the day of his death. He also had a surname Stroyer, but he could not use it in public as the surname would be against the law; he was known only by the name William Singleton because his master's name was Singleton, so the title Stroyer was forbidden him and could be used by his children only after the emancipation of the slaves.

There were two reasons given by the slave holders why a slave should not use his own name but the name of his master, one was that if the slave were to run away into a free state he would not be so easily detected by using his own name as if he used that of his master, the second was that in allowing him to use his own name he would be sharing an honor due his master alone, and it would be too much for a negro who was nothing but a servant. So it was held as a crime for the slave to be caught using his own name and it would expose him to severe punishment, but thanks be to God those days have passed and we now live under the sun of liberty.

My mother also belonged to Col. M. R. Singleton, and was a field hand. She never was sold but her parents were once. One Mr. Crough owned the plantation where mother lived and he sold it with mother's parents and the other slaves thereon to Col. Dick Singleton.

The family from which mother came had, most of them, trades of some kind; some were carpenters, some blacksmiths, others house servants, and some were made drivers over the other negroes, of course the negro drivers would be under a white man who was called overseer. But mother had to take her chance out in the field with those who had to weather the storms. My readers are not to think that those whom I have spoken of as having trades were free from punishment, for they were not; some of them had more troubles than the field hands.

At times, when the overseer was angry with a man or a woman, he would strike them on the head with a club and kill them instantly, and they would bury them right in the field. Some would run away and come to M. R. Singleton, my master, but he would only tell them to go home and behave, then they were handcuffed or chained and carried back to Biglake [another Singleton family plantation], and when we heard from them again the greater part would have been murdered. When they were taken from master's place they would bid us good bye and say they knew they should be killed when they got home.

Oh! who can paint the sad feeling in our minds when we saw these, our own race, chained and carried home to drink the bitter cup of death from their merciless oppressors, with no one near to say, "Spare him, God made him," or to say, "Have mercy on him, for Jesus died for him." His companions dared not groan above a whisper for fear of sharing the same fate; but thanks that the voice of the Lord was heard in the North, which said, "Go quickly to the South and let my prison-bound people go free, for I have heard their cries from the cotton, corn and rice plantations, saying, how long before thou wilt come to deliver us from this chain?" And the Lord said to them, "Wait, I will send you John Brown who shall be the key to the door of your liberty, and I will harden the heart of Jefferson Davis, your devil, that I may show him and his followers my power; then shall I send you Abraham Lincoln, mine angel, who shall lead you from the land of bondage to the land of liberty." Our fathers all died in "the wilderness," but, thank God, the children reached "the promised land."

The witches among slaves were supposed to have been persons who worked with them every day, and were called old hags or jack lanterns. Those, both men and women, who, when they grew old looked odd, were supposed to be witches.

[The terms "old hags" and "jack (o')lanterns" are, of course of English origin. Although Jacob Stroyer's father had come directly from Africa, his mother's family, like many others in South Carolina, had been enslaved for generations, had lost family memories of African languages, and had adopted English terms for magic. As in Virginia and other Southern states along the Atlantic Ocean, the word "witches" was widely used by black people in South Carolina to describe those who practiced magic.

Sometimes after eating supper the negroes would gather in each other's cabins which looked over the large openings on the plantation, and when they would see a light at a great distance and saw it open and shut they would say "there is an old hag," and if it came from a certain direction where those lived whom they called witches, one would say "dat looks like old Aunt Susan," another said "no, dat look like man hag," still another "I tink dat look like ole Uncle Renty."

When the light disappeared they said that the witch had got into the plantation and changed itself into a person, and went around on the place talking with the people like others until those whom it wanted to bewitch went to bed, then it would change itself to a witch again. They claimed that they rode human beings like horses, and the spittle that run on the side of the cheek when one slept was the bridle that the witch rode with.

Sometimes a baby would be smothered by its mother and they would charge it to a witch. If they went out hunting at night and were lost it was believed that a witch led them off, especially if they fell into a pond or creek. I was very much troubled with witches when a little boy and am now sometimes, but it is only when I eat a hearty supper and then go to bed.

It was said by some of the slaves that the witches would sometimes go into the rooms of the cabins and hide themselves until the family went to bed, and when any one claimed that they went into the apartment before bed time and thought he saw a witch, if they had an old Bible in the cabin that would be taken into the room and the person who carried the Bible would say as he went in "In de name of de Fader and of de Son and de Hole Gos' wat you want?" then the Bible would be put in the corner where the person thought he saw the witch, as it was generally believed that if this were done the witch could not stay.

When they could not get the Bible they used red pepper and salt pounded together and scattered in the room, but in this case they generally felt the effects of it more than the witch, for when they went to bed it made them cough all night.

When I was a little boy my mother sent me into the cabin room for something, and as I got in I saw something black and white, but did not stop to see what it was, and running out said there was a witch in the room, but father having been born in Africa did not believe in such things, so he called me a fool and whipped me and the witch got scared and ran out of the door; it turned out to be our own black and white cat that we children played with every day. Although it proved to be the cat, and father did not believe in witches, still I held the idea that there were such things, for I thought as the majority of the people believed it that they ought to know more than one man.

Sometime after I was free, in traveling from Columbia to Camden, a distance of about thirty-two miles; night overtook me when about half way there, it was very dark and rainy, and as I approached a creek I saw a great number of lights of those witches opening and shutting, I did not know what to do and thought of turning back, but when I looked behind I saw some witches in the distance, so I said if I turn back those will meet me and I will be in as much danger as if I go on, and I thought of what some of my fellow negroes had said about their leading men into ponds and creeks; there was a creek just ahead, so I concluded that I should be drowned that night, however I went on, as I saw no chance of turning back. When I came near the creek one of the witches flew into my face; I jumped back and grasped it, but it proved to be one of those little lightning bugs, and I thought if all the witches were like that one I should not be in any great danger from them.

The slaves had three ways of detecting thieves, one with a Bible, one with a sieve, and another with graveyard dust.

[The first two methods as European forms of divining the name of a thief, which were added to the African repertoire of divination after enslavement, for neither the Bible nor the sieve and scissors were African in origin, and both methods are found extensively in England, Ireland, Scotland, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. Stroyer seems to have been aware of this, for he rightly described the method of ascertaining the name of a thief by the drinking of graveyard dust in water as a practice "taught by the fathers and mothers of the slaves," perhaps even by his own father, who had been born in Sierra Leone.]

The first way was this: Four men were selected, one of whom had a Bible with a string attached, and each man had his own part to perform. Of course this was done in the night, as it was the only time they could attend to such matters as concerned themselves. These four would commence at the first cabin with every man of the family, and one who held the string attached to the Bible would say, "John or Tom," whatever the person's name was "you are accused of stealing a chicken or a dress from Sam at such a time," then one of the other two would say, "John stole the chicken," and another would say, "John did not steal the chicken."

They would continue their assertions for at least five minutes, then the man would put a stick in the loop of the string that was attached to the Bible, and holding it as still as they could, one would say, "Bible, in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost, if John stole that chicken, turn," that is, if the man had stolen what he was accused of, the Bible was to turn around on the string, and that would be a proof that he did steal it. This was repeated three times before they left that cabin, and it would take those men a month sometimes when the plantation was very large, that is, if they did not find the right person before they got through the whole place.

The second way they had of detecting thieves was very much like the first, only they used a sieve instead of a Bible; they stuck a pair of scissors in the sieve with a string hitched to it and a stick put through the loop of the string and the same words were used as for the Bible.

Sometimes the Bible and the sieve would turn upon names of persons whose characters were beyond suspicion. When this was the case they would either charge the mistake to the men who fixed the Bible and the sieve, or else the man who was accused by the turning of the Bible and the sieve would say that he passed near the coop from which the fowl was stolen, then they would say, "Bro. John we see dis how dat ting work, you pass by de chicken coop de same night de hen went away."

But when the Bible or the sieve turned on the name of one whom they knew often stole, and he did not acknowledge that he stole the chicken of which he was accused, he would have to acknowledge his previously stolen goods or that he thought of stealing at the time when the chicken or dress was stolen. Then this examining committee would justify the turning of the Bible or sieve on the above statement of the accused person.

The third way of detecting thieves was taught by the fathers and mothers of the slaves. They said no matter how untrue a man might have been during his life, when he came to die he had to tell the truth and had to own everything that he ever did, and whatever dealing those alive had with anything pertaining to the dead, must be true, or they would immediately die and go to hell to burn in fire and brimstone, so in consequence of this, the graveyard dust was the truest of the three ways in detecting thieves.

The dust would be taken from the grave of a person who died last [the most recently deceased person ] and put into a bottle and water was put into it. Then two of the men who were among the examining committee would use the same words as in the case of the Bible and the sieve, that is, one would say, "John stole that chicken," another would say, "John did not steal that chicken;" after this had gone on for about five minutes, then one of the other two who attended to the Bible and the sieve would say, "John, you are accused of stealing that chicken that was taken from Sam's chicken coop at such a time," and he would say, "In the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost, if you have taken Sam's chicken, don't drink this water, for if you do you will die and go to hell and be burned in fire and brimstone, but if you have not, you may take it and it will not hurt you." So if John had taken the chicken he would own it rather than take the water.

Sometimes those whose characters were beyond suspicion would be proven thieves when they tried the graveyard dust and water.

When the right person was detected, if he had any chickens he had to give four for one, and if he had none he made it good by promising him that he would do so no more. If all the men on the plantation passed through the examination and no one was found guilty, the stolen goods would be charged to strangers.

Of course these customs were among the negroes for their own benefit, for they did not consider it stealing when they took anything from their master.

This material is reprinted from

Sketches of My Life in the South

Jacob Stroyer

Salem [Massachusetts]

Printed at the Salem Press

1879

[My sincere gratitude to nagasiva yronwode for helping with graphics.]

Search All Lucky Mojo and Affiliated Sites!

You can search our sites for a single word (like archaeoastronomy, hoodoo, conjure, or clitoris), an exact phrase contained within quote marks (like "love spells", "spiritual supplies", "occult shop", "gambling luck", "Lucky Mojo bag", or "guardian angel"), or a name within quote marks (like "Blind Willie McTell", "Black Hawk", "Hoyt's Cologne", or "Frank Stokes"):

|

|

copyright ©

1994-2021 catherine yronwode. All rights reserved. Send your comments to: cat yronwode. |

|

Did you like what you read here? Find it useful? Then please click on the Paypal Secure Server logo and make a small donation to catherine yronwode for the creation and maintenance of this site. |

|

This website is part of a large domain that is organized into a number of interlinked web sites, each with its own distinctive theme and look. You are currently reading SOUTHERN SPIRITS by cat yronwode . |

Here are some other LUCKY MOJO web sites you can visit:

OCCULTISM, MAGIC SPELLS, MYSTICISM, RELIGION, SYMBOLISM

Hoodoo in Theory and Practice by cat yronwode: an introduction to African-American rootwork

Hoodoo Herb and Root Magic by cat yronwode:a materia magica of African-American conjure

Lucky W Amulet Archive by cat yronwode: an online museum of worldwide talismans and charms

Sacred Sex: essays and articles on tantra yoga, neo-tantra, karezza, sex magic, and sex worship

Sacred Landscape: essays and articles on archaeoastronomy and sacred geometry

Freemasonry for Women by cat yronwode: a history of mixed-gender Freemasonic lodges

The Lucky Mojo Esoteric Archive: captured internet text files on occult and spiritual topics

Lucky Mojo Usenet FAQ Archive:FAQs and REFs for occult and magical usenet newsgroups

Aleister Crowley Text Archive: a multitude of texts by an early 20th century occultist

Lucky Mojo Magic Spells Archives: love spells, money spells, luck spells, protection spells, and more

Free Love Spell Archive: love spells, attraction spells, sex magick, romance spells, and lust spells

Free Money Spell Archive: money spells, prosperity spells, and wealth spells for job and business

Free Protection Spell Archive: protection spells against witchcraft, jinxes, hexes, and the evil eye

Free Gambling Luck Spell Archive: lucky gambling spells for the lottery, casinos, and racesPOPULAR CULTURE

Hoodoo and Blues Lyrics: transcriptions of blues songs about African-American folk magic

EaRhEaD!'S Syd Barrett Lyrics Site: lyrics by the founder of the Pink Floyd Sound

The Lesser Book of the Vishanti: Dr. Strange Comics as a magical system, by cat yronwode

The Spirit Checklist: a 1940s newspaper comic book by Will Eisner, indexed by cat yronwode

Fit to Print: collected weekly columns about comics and pop culture by cat yronwode

Eclipse Comics Index: a list of all Eclipse comics, albums, and trading cardsEDUCATION AND OUTREACH

Hoodoo Rootwork Correspondence Course with cat yronwode: 52 weekly lessons in book form

Hoodoo Conjure Training Workshops: hands-on rootwork classes, lectures, and seminars

Apprentice with catherine yronwode: personal 3-week training for qualified HRCC graduates

Lucky Mojo Community Forum: an online message board for our occult spiritual shop customers

Lucky Mojo Hoodoo Rootwork Hour Radio Show: learn free magic spells via podcast download

Lucky Mojo Videos: see video tours of the Lucky Mojo shop and get a glimpse of the spirit train

Lucky Mojo Publishing: practical spell books on world-wide folk magic and divination

Lucky Mojo Newsletter Archive: subscribe and receive discount coupons and free magick spells

LMC Radio Network: magical news, information, education, and entertainment for all!

Follow Us on Facebook: get company news and product updates as a Lucky Mojo Facebook FanONLINE SHOPPING

The Lucky Mojo Curio Co.: spiritual supplies for hoodoo, magick, witchcraft, and conjure

Herb Magic: complete line of Lucky Mojo Herbs, Minerals, and Zoological Curios, with sample spells

Mystic Tea Room Gift Shop: antique, vintage, and contemporary fortune telling tea cupsPERSONAL SITES

catherine yronwode: the eclectic and eccentric author of many of the above web pages

nagasiva yronwode: nigris (333), nocTifer, lorax666, boboroshi, Troll Towelhead, !

Garden of Joy Blues: former 80 acre hippie commune near Birch Tree in the Missouri Ozarks

Liselotte Erlanger Glozer: illustrated articles on collectible vintage postcards

Jackie Payne: Shades of Blues: a San Francisco Bay Area blues singerADMINISTRATIVE

Lucky Mojo Site Map: the home page for the whole Lucky Mojo electron-pile

All the Pages: descriptive named links to about 1,000 top-level Lucky Mojo web pages

How to Contact Us: we welcome feedback and suggestions regarding maintenance of this site

Make a Donation: please send us a small Paypal donation to keep us in bandwidth and macs!OTHER SITES OF INTEREST

Arcane Archive: thousands of archived Usenet posts on religion, magic, spell-casting, mysticism, and spirituality

Association of Independent Readers and Rootworkers: psychic reading, conjure, and hoodoo root doctor services

Candles and Curios: essays and articles on traditional African American conjure and folk magic, plus shopping

Crystal Silence League: a non-denominational site; post your prayers; pray for others; let others pray for you

Gospel of Satan: the story of Jesus and the angels, from the perspective of the God of this World

Hoodoo Psychics: connect online or call 1-888-4-HOODOO for instant readings now from a member of AIRR

Missionary Independent Spiritual Church: spirit-led, inter-faith; prayer-light services; Smallest Church in the World

Mystic Tea Room: tea leaf reading, teacup divination, and a museum of antique fortune telling cups

Satan Service: an archive presenting the theory, practice, and history of Satanism and Satanists

Southern Spirits: 19th and 20th century accounts of hoodoo, including ex-slave narratives & interviews

Spiritual Spells: lessons in folk magic and spell casting from an eclectic Wiccan perspective, plus shopping

Yronwode Home: personal pages of catherine yronwode and nagasiva yronwode, magical archivists

Yronwode Institution: the Yronwode Institution for the Preservation and Popularization of Indigenous Ethnomagicology